Quantum Technology Companies: patent analysis

Quantum computing patent applications have increased significantly since 2009, reflecting the growing maturity and industrial relevance of the field.

Patent intelligence for people who don't read patents

However, for those without a background in patents, or the means to access patent analytics, it’s not always clear what this growth in patents means for strategy, innovation, or competition.

To address this we are publishing the Quantum Technology Companies: Patent Report 2025. The report will be available at the end of September 2025.

The report aims to translates complex patent data into clear, decision-useful insights—designed for people who don’t read patents but need to understand what they reveal.

So whether you're tracking competitors, exploring partnerships, or planning R&D strategy, this report offers practical patent intelligence without legal jargon or technical complexity.

Sharing insights as we progress

As our research progresses towards the release of the report I’ll be sharing selected findings from the research conducted so far for the Quantum Technology Companies: Patent Report 2025.

This week's analysis

We take a company-first approach for analysis

Patent analysis is often organised around technology categories. While this is useful for understanding which types of technologies are being developed, it doesn’t explain how individual companies are innovating overall, or how they may compete now and in the future.

This report takes a company-first approach. Technologies are still analysed, but only in the context of which companies are working in those areas and how their portfolios are evolving.

Patent activity in quantum computing comes from a wide mix of organisations — not just start-ups or tech giants. To make sense of this, the report classifies all quantum technology developers into four broad groups: quantum-first companies, nonquantum-first companies, academic institutions, and government agencies. Each group plays a different role in the quantum ecosystem, with distinct motivations for filing patents — whether to build products, secure strategic positioning, generate knowledge, or shape national policy.

Quantum technology developers

Quantum-first companies

Companies that are founded specifically to develop quantum technologies — such as quantum hardware, software, or algorithms. Quantum computing is their core business and reason for existence.

- Examples: IonQ, Rigetti, PsiQuantum, Oxford Quantum Circuits

- Key traits: Born-quantum, deep tech R&D, often start-ups or spinouts

- Focus: Building quantum systems from the ground up, applying quantum to existing problems (e.g., optimisation, simulation, cryptography)

Nonquantum-first companies

Companies whose core business was built on classical technologies, but are now adopting or investing in quantum computing for strategic purposes. Quantum is not their origin, but a new direction.

- Examples: Google, Microsoft, Siemens, JPMorgan Chase, Accenture

- Key traits: Classical roots, large-scale infrastructure, quantum is an extension

- Focus: Applying quantum to existing problems (e.g., optimisation, simulation, cryptography), building quantum systems from the ground up

Academic Institutions

Organisations primarily focused on education and fundamental research. They play a critical role in advancing quantum science, often producing early-stage innovations that later lead to patents, spinouts, or collaborations with industry. While not commercial entities, many contribute significantly to the quantum patent landscape.

- Examples: University of Cambridge, TU Delft, Yale University, MIT

- Key traits: Research-driven, non-commercial, publish-first culture, often source of spinouts

- Focus: Fundamental research, talent development, IP generation

Government Agencies

Public bodies responsible for funding, coordinating, and sometimes directly conducting quantum research. They help set national agendas, provide infrastructure support, and maintain strategic oversight. Some agencies also operate government labs or hold patents, but their role is typically to enable — not commercialise — quantum development.

- Examples: DARPA, NIST, CSIRO, Dstl, Fraunhofer, IMEC

- Key traits: Policy-driven, non-commercial, long-term focus, national interest

- Focus: Funding, coordination, standards, and strategic national capability

We will classify every patent applicant as one of these four groups.

Identifying quantum technology patents to include

We took a simple and straightforward approach and use patent classification codes to identify those patents of interest.

What are patent classification codes?

Patent classification codes are used to organise and tag patents based on the type of technology they describe — a bit like how libraries use subject categories for books.

Two main systems are used globally:

CPC – Cooperative Patent Classification

- Developed by the European Patent Office (EPO) and the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)

- Offers fine-grained detail — especially useful for emerging technologies like quantum computing

- Often used by analysts, researchers, and patent examiners for searching and grouping similar inventions

IPC – International Patent Classification

- Managed by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

- Used globally across all patent offices

- Provides broader categories compared to CPC

- Helps standardise how technologies are classified worldwide

When a company files a patent, it gets assigned one or more of these codes based on the technology it covers. In quantum computing, classification codes help:

- Group similar patents together

- Track developments in specific technical areas

- Compare activity across regions or organisations

Why are classification codes useful for searching?

Patent documents are often technical, long, and written in very different ways — even when they describe similar ideas. This makes keyword searching unreliable on its own.

Classification codes solve this by acting like filters.

They group patents by technology, not just by the words used in the text.

So if you're looking for:

- All patents about quantum error correction, or

- Everything filed under quantum key distribution (QKD)

—you can search by classification code to find relevant patents, even if different companies describe the same thing in very different language.

Patent classification codes relevant to quantum computing

CPC (Cooperative Patent Classification)

These are more detailed codes used primarily by the EPO and USPTO:

- G06N 10/20 – Models of quantum computing (e.g. quantum circuits, universal quantum computers)

- G06N 10/40 – Physical architectures for quantum processors (e.g. qubit control, superconducting, ion traps)

- G06N 10/60 – Quantum algorithms (e.g. Grover’s, Shor’s, quantum optimisation, hybrid approaches)

- G06N 10/70 – Quantum error correction (e.g. surface codes, fault tolerance)

- G06N 10/80 – Quantum programming and platforms (e.g. SDKs, quantum languages, cloud-based access)

IPC (International Patent Classification)

A broader, globally-used system, with general categories relevant to quantum:

- G06N 10/00 – Quantum computing overall (covers models, hardware, algorithms, etc.)

The patent dataset

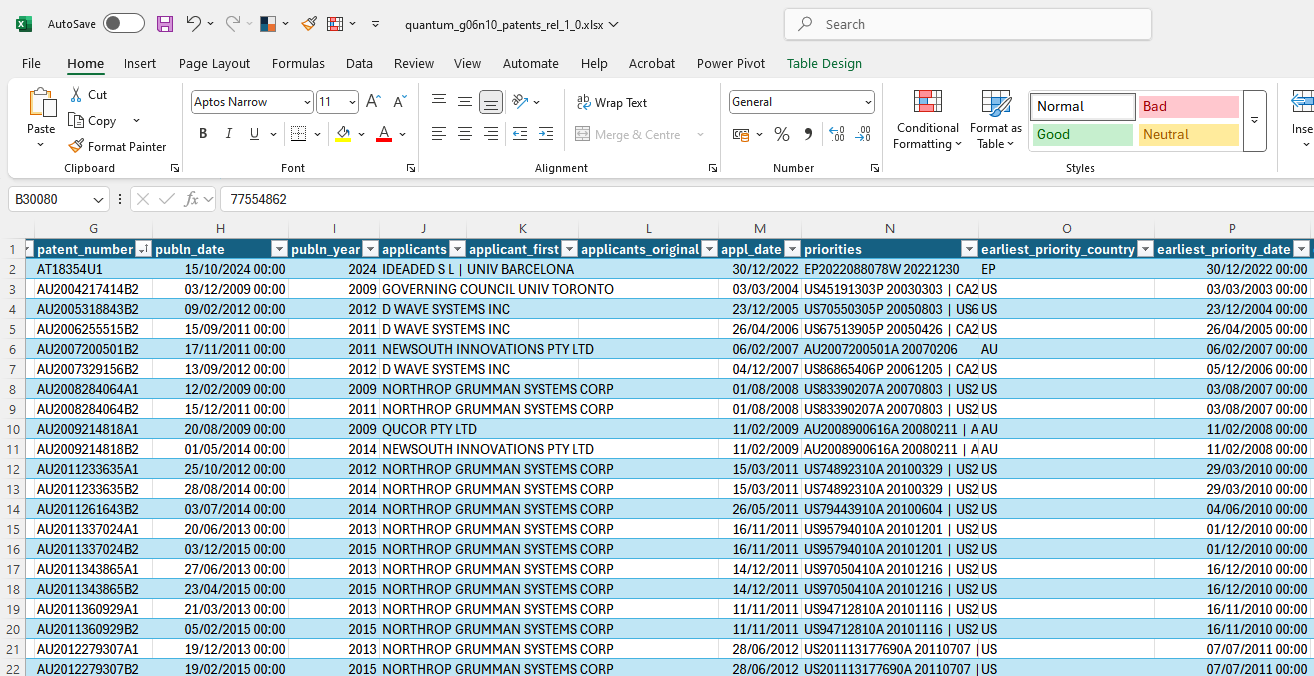

The quantum computing patent dataset was built by searching DOCDB, the EPO’s main patent database. The search looked for any record with one or more of the CPC or IPC classification codes mentioned earlier, and that had been published since January 2009.

It returned just over 30,000 patent records. These include early-stage applications, granted patents, and various corrections. This is the raw dataset — I’ll be cleaning and refining it as the research goes on.

Right now, the data sits in a local database, which I use to run structured searches and groupings. I also export parts of it into Excel — a spreadsheet provides a quick and easy way to scan through applicants or technologies in bulk.

From filing to grant: How patents progress

When a company files a patent application, it’s marking the point in time when it first claims an invention. This is called the filing date, and it starts the formal review process.

Often, the company will first file in its home country. That initial application is known as the priority filing, and the priority date is the official timestamp of the invention. Any later filings in other countries (for the same invention) will usually refer back to that date.

After a delay — typically 18 months — the application is made public. This is called the first publication date, and it’s the point where the details of the invention become visible to others.

Once filed, the application enters a structured review. This is handled by patent examiners — trained specialists at the patent office. Their job is to assess whether the invention meets the legal requirements for patent protection. That includes checking if it’s new, inventive, clearly described, and doesn’t overlap with earlier patents.

This review process — often called prosecution — can involve questions, objections, rewording, or technical clarifications. It’s a back-and-forth between the applicant and the examiner.

In the end, one of several outcomes is possible:

- The patent is granted, giving the applicant legal protection

- The application is withdrawn, either voluntarily or due to inactivity

- Or the record is updated through corrections or formal amendments

This process can take two to five years or more, depending on the complexity and the patent office involved.

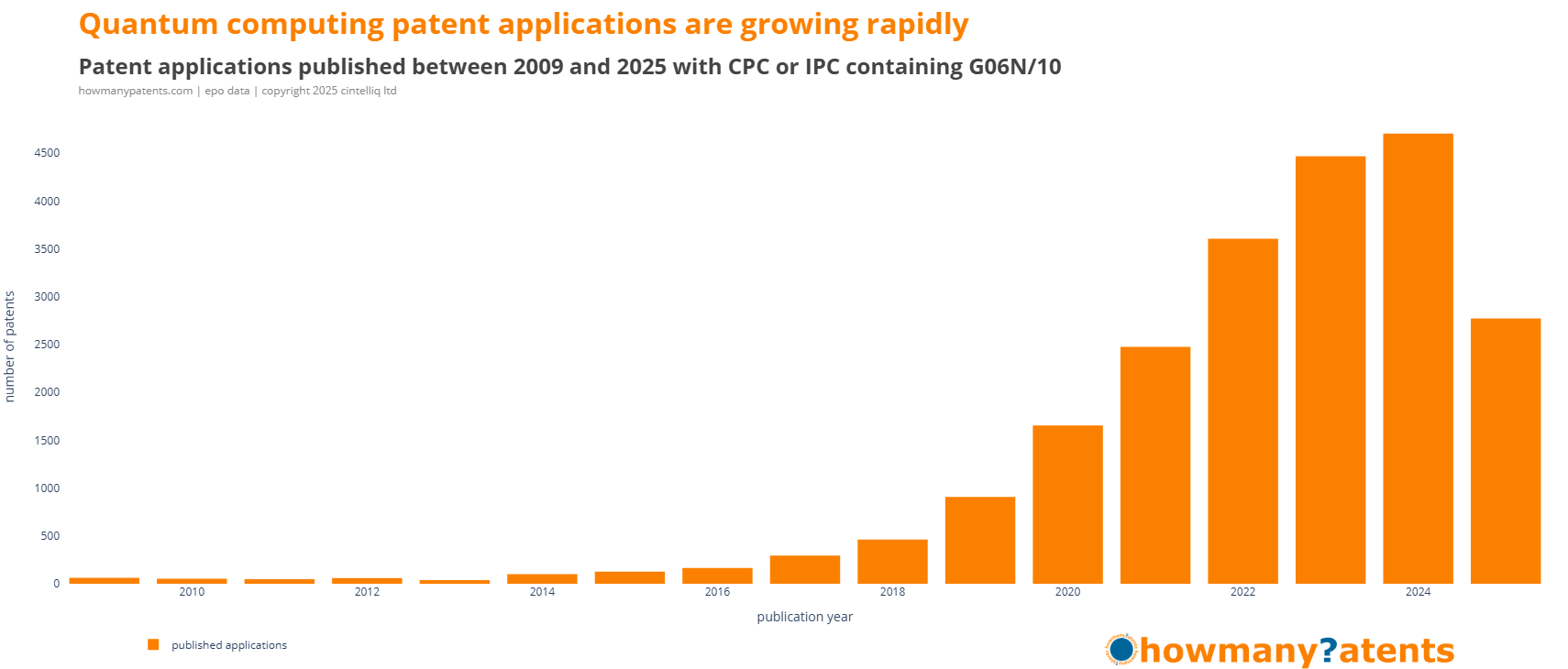

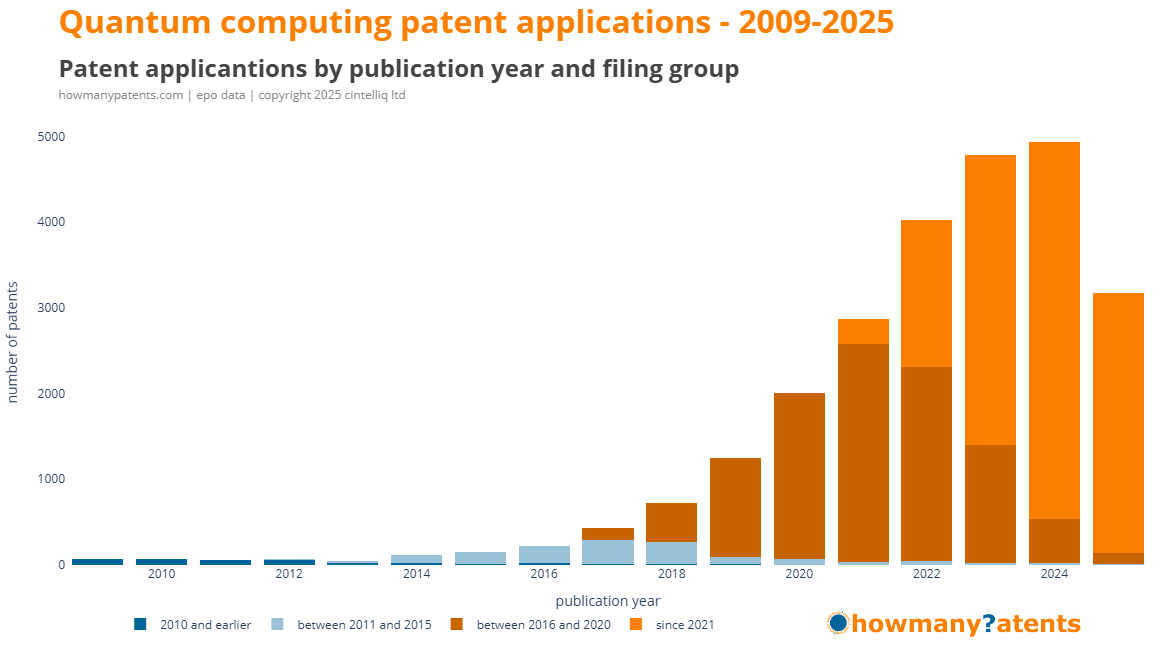

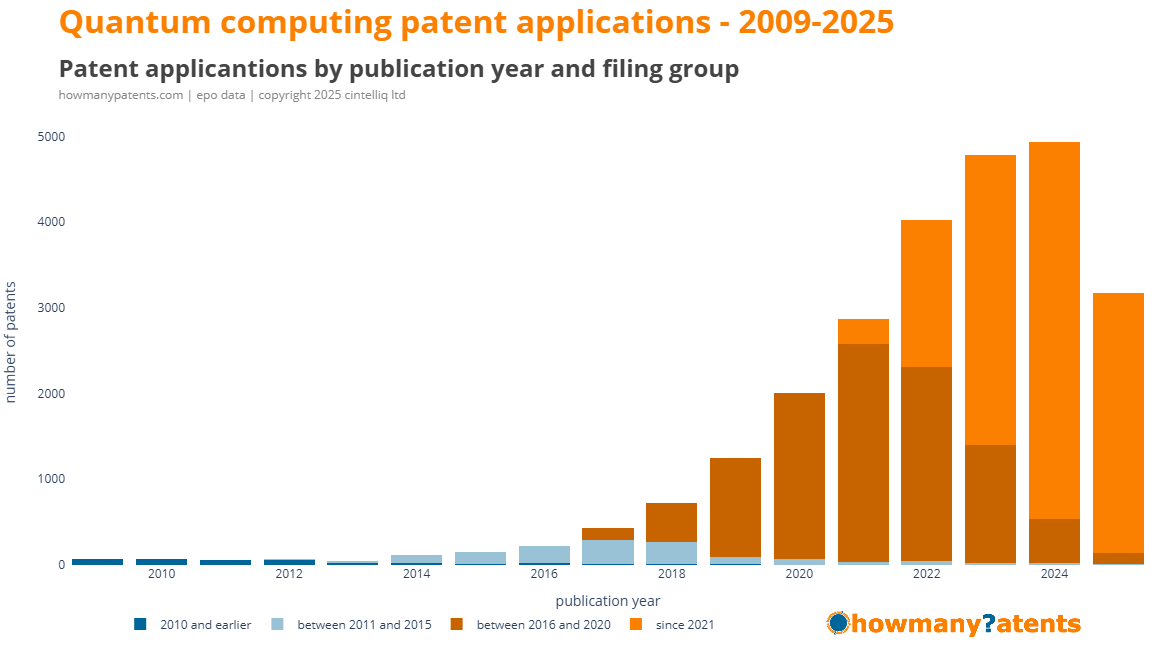

Patent applications by publication date

The chart below shows the number of quantum computing patent applications published each year since 2009. There’s a clear upward trend, with published patent applications growing rapidly over time.

Note that the data for 2025 only covers the first six months of the year.

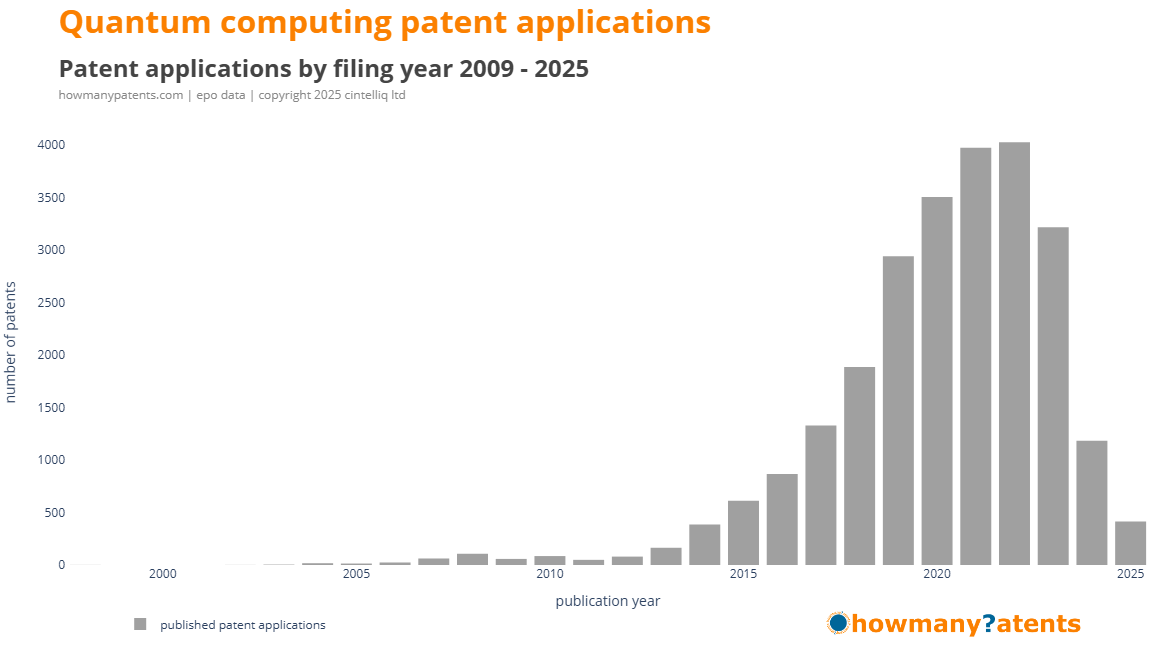

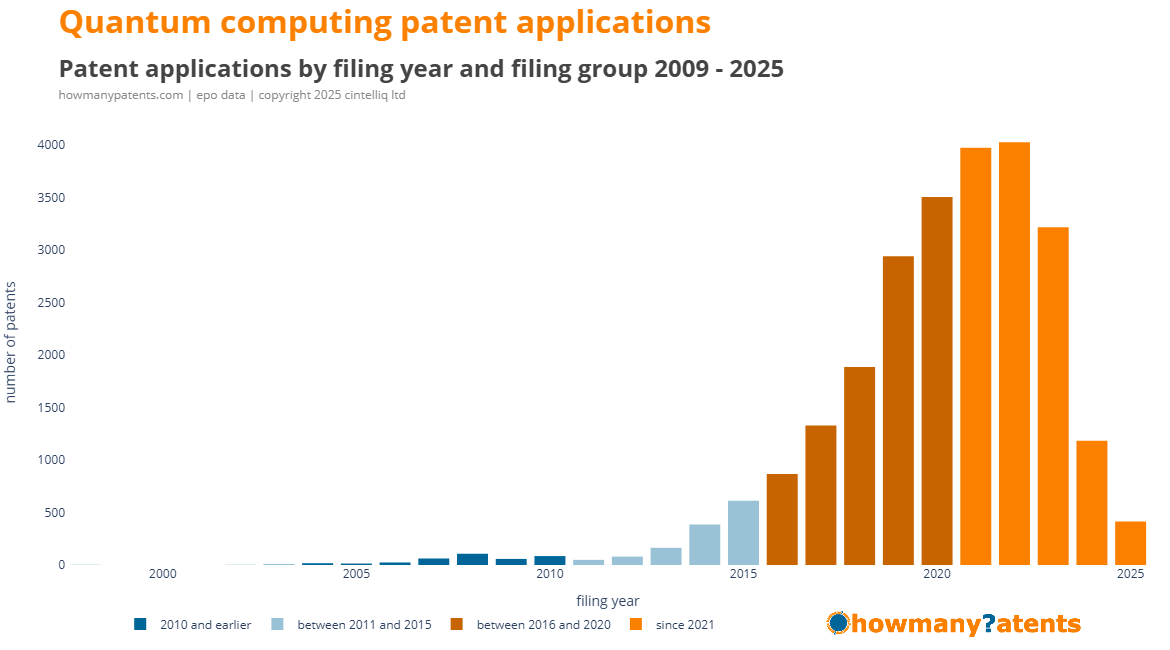

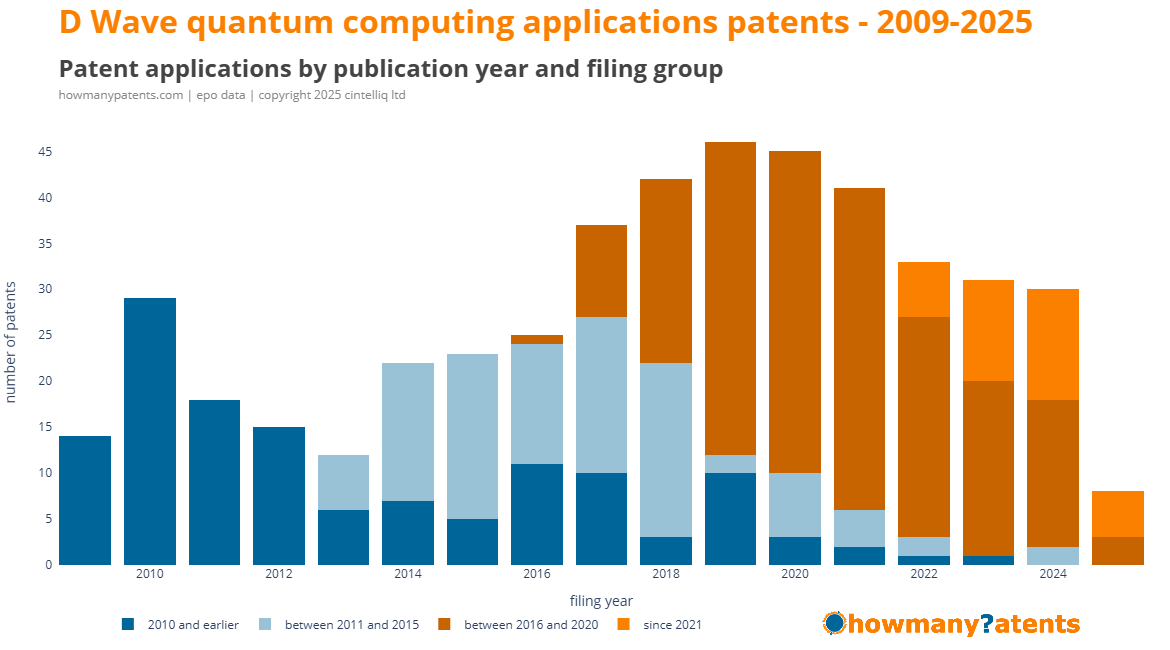

Patent applications by filing year

Another way to look at patent activity is by the year the initial application was filed. This gives a clearer view of when the invention was first claimed — and is often used as a way of dating the invention itself.

The filing date is usually also the priority date — the earliest official timestamp for that invention.

To help with analysis, I’ve colour-coded the filing dates in four groups: before 2009, 2010–2015, 2016–2020, and 2021 onwards.

Patent applications by publication and priority grouping

Colour-coding the applications by filing year becomes more useful when combined with publication year. Plotting them this way shows how many patents were published each year, grouped by when they were actually filed.

This highlights an important point: a patent published this year might relate to an invention filed — and originally developed — several years earlier.

You can see this clearly in the group of patents filed between 2016 and 2020. Many of them were still being published as late as 2025, even though the peak publication year was 2021.

Let's take a look at these for a single company

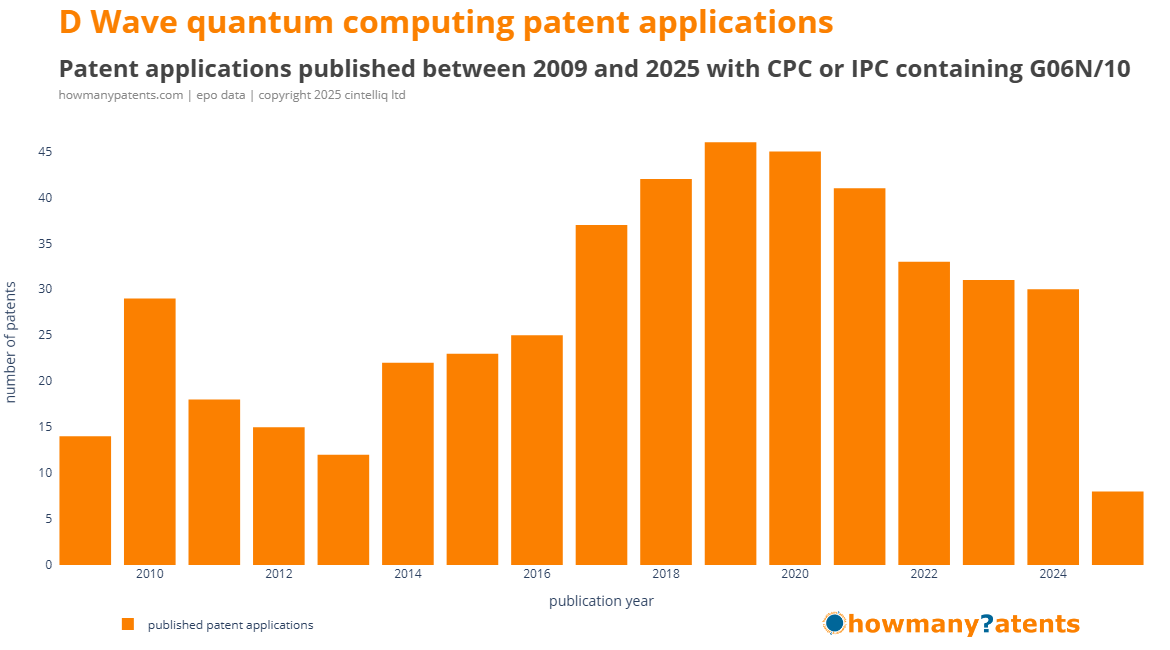

For this example I've chosen D-Wave for analysis. According to the company's website D-Wave was founded in 1999, and consider themselves as a leader in the development and delivery of quantum computing systems, software, and services. They also claim to be the world’s first commercial supplier of quantum computers.

D-Wave has 407 patent applications published between 2009 and mid-2025.The number of published patent applicants grew steadily between 2014 and peaked in 2020.

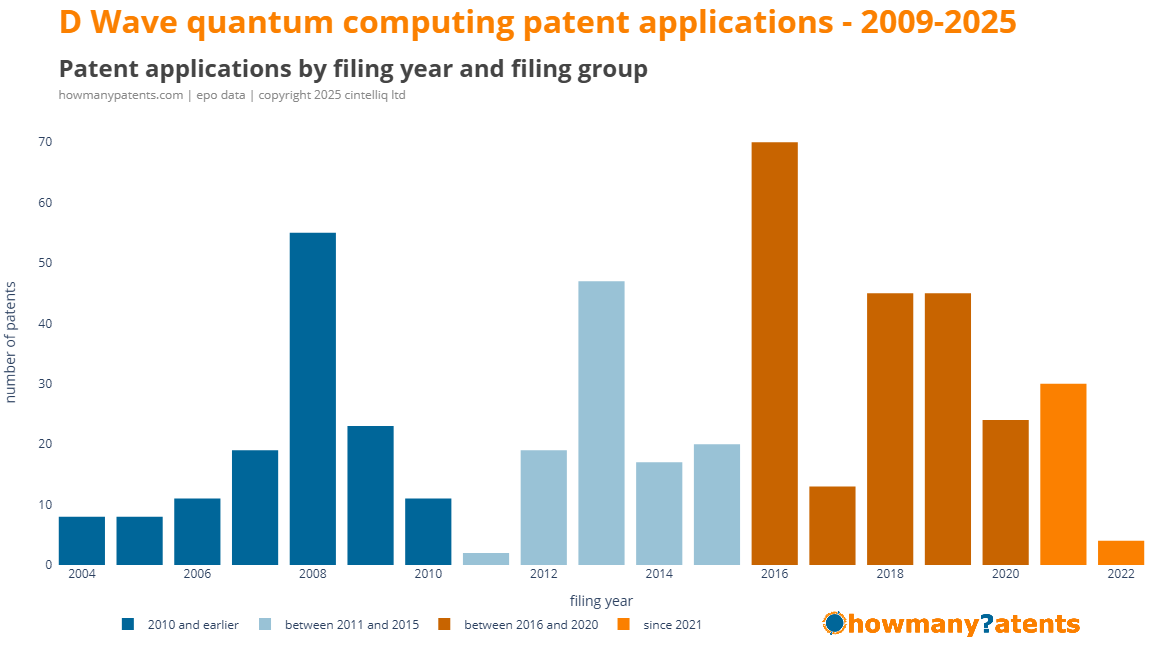

Looking at the patent applications by filing year shows patent activity has shifted over time. Since 2016, D-Wave has filed 216 patent applications,

Since 2016 D-Wave has filed 216 patent applications:

- 100 patent applications filed in 2010 and earlier

- 91 patent applications filed between 2011 and 2015

- 182 patent applications filed between 2016 and 2020

- 34 patent applications filed from 2021 onwards

The chart below also shows that even the most recent published patent applications all relate to inventions filed in 2022 or earlier. That’s due to the typical delay — usually around 18 months — between filing and publication.

This highlights an important point: a patent published this year might relate to an invention filed — and originally developed — several years earlier.

Taken together with the drop in filings since 2021, this could suggest a slowing in D-Wave’s innovation pipeline. It may also be due in part to international expansion, that is another piece of the analysis which I will discuss next week.

Finally,

It’s important to note that even if a company has a lot of patent applications published in a short time frame, that doesn’t mean the inventions are recent.

Patent analysis is a bit like astronomy — we’re looking at past activity to understand what’s happening now, and even into the future.

Next insights

We will look further at the patent dataset in terms of

- publication country

- filing country

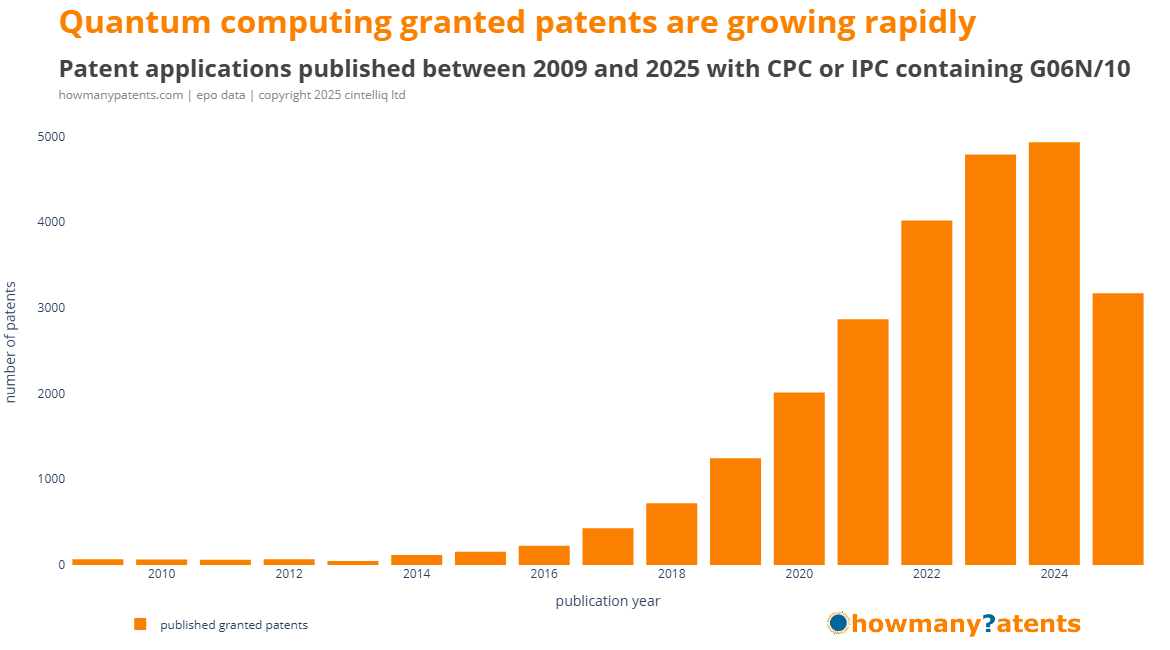

- granted patents

- patent families

Quantum Technology Companies: Patent Report 2025

Pre-order your copy today

The report will be available to purchase in late September 2025.

Pre-order, and pay, for the Quantum Technology Companies: Patent Report 2025.